History and Archaeology

Bruntsfield Links

Situation: Bounded by the south side of Melville Drive and extending beyond Whitehouse Loan to Bruntsfield Place, Terrace and Crescent.

Area: 36.2 acres (14.661 hectares)

Bruntsfield Links is the easterly part of what was the famous old Borough Muir, wherein 1513 King James IV reviewed his troops before they set off to the fatal field of Flodden. The Borough Muir or Myre, was gifted to the 'Magistrates, Council and Community of the City' by David 1 of Scotland and once extended westwards from what is now the Dalkeith Road area Merchiston, and southwards to the Pow Burn.

In those ancient times, not only did the moor abound with oak trees, but outlaws and Edinburgh outcasts made it their home. It was not a place to be caught after dark, but the Scottish nobility once used it for their hunting ground, when deer and wild boar were plentiful.

"Great stone quarries" are recorded on the site and old Edinburgh Town Centre minutes indicate that one Patrick Carfrae, deacon of the masons, was given permission to dig for stones there in 1599. Quarrying continued on the Links for at least 200 years and rightful concern was expressed from time to time about their depth and danger.

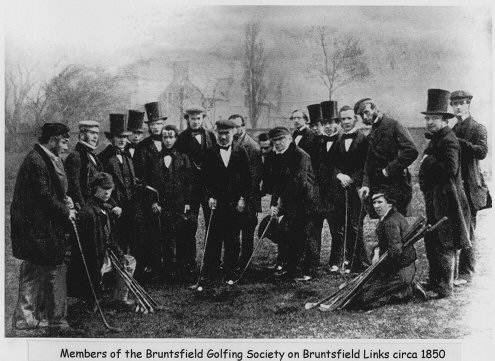

Up to 1878 is was upheld by the magistrates and Council as a portion of Common Good property and in 1741 an important priority was declared in the contract with John Hog, who had been given permission to "dig for stanes" for the refurbishment of tenements at the Luckenbooths. On no account, he was instructed, must he interfere in any way or on any part of the Links used for "the citizens' diversion and recreation in the golf".

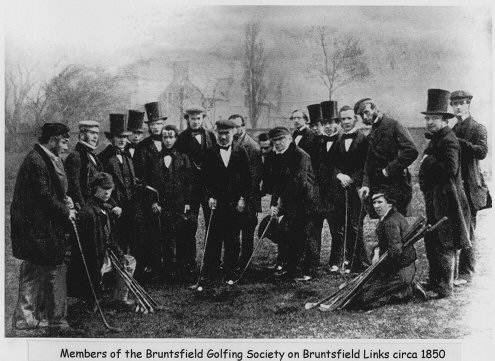

"The Gowf" took precedence over everything, from stopping a road being built through the park to the prevention of exercising horses. Even Sir Walter Scott, in his capacity as secretary of the Royal Edinburgh Light Dragoons, was informed that drilling his troops on the Links' most hallowed golfing turf would not be permitted. The Links became the home of several golf clubs, the most ancient being today's Royal Burgess club, which traces its roots back to 1735.

As the city expanded and increasing fues were allocated, first houses and then the streets began to eat into this important green space, until the Edinburgh Improvement Act of 1827 called a halt to the encroachment. Those dearly-defended 30 acres today are one of the prides of the Bruntsfield area with their splendid presentations of elm, sycamore, maple, ash, lime, white beam and other varieties like cherry, hawthorn, chestnut, crab apple and oak. They make summer a visual treat. Apart from a stone seat at the highest point, bearing initials and several dates, the oldest being 1848, there are no reminders of the past. Even the once popular putting green at Bruntsfield Place has now gone. But like those ancient golfers who swung their way with vigour across the Links that same pleasure of a stroll over one of Edinburgh's green delights continues today for local residents and visitors alike.

Facilities: Short golf course, walks, benches and toilets. On bus route. Access for disabled.

The Meadows

Situation: To the north side of Melville Drive.

Area: 58.4 acres (22.032 hectares).

The Meadows remain one of the most important open spaces in Edinburgh and one of the most popular. In a city built on hills, the flat, wide-open green sward of the Meadows, set in a treescape of more than 1,200 elm, sycamore, maple, ash, lime, beech, cherry willow, poplar, chestnut, oak and other varieties, the enfolding south side of the city in dramatic skyline silhouette, with sweeping panoramas beyond, conjure sharp and pleasing contrasts - yet it is less than a mile from Princes Street. This was once the site of the wind-swept Borough-Loch, which was part of the historic old Borough Muir and one of the main water supplies for Edinburgh's Old Town.

As the years passed, the loch took three names: the Borough Loch; the South Loch to draw the distinction with the North Loch, now occupied by the railway line at the foot of the Castle Rock in Princes Street Gardens; then Stration's Loch after John Stration, who unsuccessfully attempted to drain it and the surrounding marshlands in 1658.

In the olden days the loch was inevitably used for washing animals and, when no one was looking, a depository for rubbish of all kinds, in spite of it being a water supply and dumping strictly forbidden.

In times of drought the quality of the water dropped with the level of the loch and a dyke was built at Lochrin to try to contain and control the water. It is recorded that a vandal of ancient times was jailed for knocking down part of the Lochrin dyke.

In 1722 the Loch was leased to Thomas Hope of Rankeillour for 57 years at the annual rent of £800 Scots. Hope's task was to complete the drainage, create a 24-foot wide walk, enclosed by a hedge and a row of trees on each side; build a 30-foot wide walkway from north to south, lined by a hedge and lime trees, with a narrow canal on nine feet on each side.

The suggested names for the new park were Hope's Park, after the lessee, or The Meadow. Almost three centuries later, both names live on in Hope Park Crescent and Hope Park Terrace and today the Meadows, intersected by Middle Meadow Walk (opened in 1743), Jawbone Walk and Coronation Walk, are properly in the plural.

From the beginning, the Meadows was another Edinburgh delight. Capital citizens came to admire and walk its surrounds of "one mile and a-half and 135syards English measure".

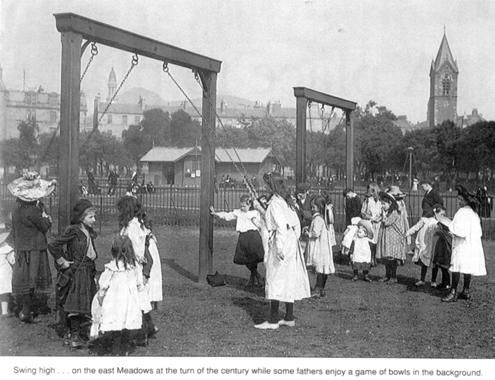

When Melville Drive was opened in 1859 as part of the South Side development, it brought a further wave of popularity and at weekends, in particular, a steady procession of carriages brought the great and the good of the city to walk or play or picnic as families, parade in the latest fashions or push perambulator to provide Edinburgh's future generations with " the fresh and scented air of "The Meadows".

As the city grew, even then threatening precious green places, the far -sighted "environmentalists" of their day saw the need for protection. The Edinburgh Improvement Act of 1827 stipulated that "should not be competent for the Lord Provost, Magistrates and Council, or any other person, without the sanction of Parliament obtained for the express purpose, at any time thereafter to erect buildings of any kind upon any part of the grounds called the Meadows or Bruntsfield Links so far as the same belong in property to the Lord Provost, Magistrates and Council".

Further later acts reinforced this firm statement and when the Commissioners of Police leased the Meadows for a period of 39 years in 1853, undertaking to keep them as a Public Park but relieving the Corporation of all costs and burdens, it was acknowledged that they had passed into safe keeping.

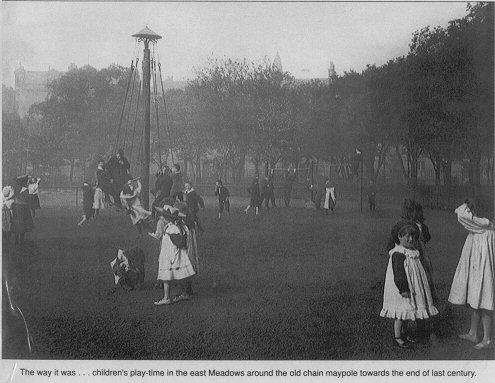

Over the centuries the Meadows have provided Edinburgh's sports men and women a full range of activities. From football, bowling, tennis, cricket, croquet, quoiting, a strip for toxopholite clubs (as archery was once called) and even target practice for the Royal Company of Archers themselves. Hundreds turned up for the old bandstand concerts, but plans for a Meadows racecourse were turned down in 1842. When the great International Exhibition of Industry, Science and Art was held in the West Meadows during the summer 1886, Edinburgh and its Meadows site were given worldwide recognition.

Still in the West Meadows, commemorating the opening of the exhibition, of an interesting and important piece of sculpture. The Prince Albert Sundial is an octagonal pillar with a bronze armillary sphere atop which acts as a sundial. Eight of the 11 stone courses are from a different quarry with varying colours. From the base they are: Moat (red); Corncockle (red); Whitsome Newton (yellow); Cragg (yellow); Myreton (blue); Ballochmyte (red); Myreton (blue); and Redhall (yellow). At the top of the pillar are shields with the coronet of the Prince, the arms of the Marquis of Lothian, the cipher of the Lord Provost and with the city Arms and the Scottish Arms ant the advice: "Tak tent o' time, ere time be tint".

Likewise, at the west end of Melville Drive, the 26-feet high commemorative octagonal stone pillars from a number of quarries were erected by the Master Builder and Operative Masons of Edinburgh to mark the exhibition. They are rendered in different styles and at the tops sit 7-ft high unicorns, with 24 shields present the Arms of Scotland, England and Ireland, coats of arms of 19 Scottish burghs and the crest of the Edinburgh masons. The whale's jawbone arch at the Melville Drive end of Jawbone Walk also celebrates the exhibition and was presented by the Zetland and Fair Isle knitting stand.

Another of those unexpected and fascinating Edinburgh memorials is also situated in the Meadows. Close to the Jawbone is the little fountain dedicated to Helen Acquroff, the blind Edinburgh musician and singer who graced the city's concert halls and theatres in the second half of the 19th century. During the programme she would compose a verse or two about the guest of honour or dignitaries in the audience and, at the end of the evening, give her special rendering to the delight of everyone.

Helen Acquroff was also a force on the city's temperance platforms, when she adopted the name of Sister Cathedral and it is fittingly reflected in the inscription on the pedestal of her fountain.

Click here to go to our page about the Helen Acquroff fountain.

Situated just behind Edinburgh Royal Infirmary and close to Edinburgh University, the Meadows remain as popular as ever and continues to be a major attraction for holding all kinds of events from circuses to tented theatre. The role of the Meadows will have to be reconsidered in the future when the old Edinburgh Royal Infirmary is vacated as it moves to a new site and the new Lauriston village is created in its place.

The trees of the Meadows and the adjoining Bruntsfield Links must have the last word. They make a major impact on the city's treescape. Among those not already mentioned are cherry, crab apple, rowan, alder, birch and almond trees. It is interesting to note a third of the trees - more than 400 - are elms. Their vulnerability to the rampant Dutch Elm disease and the future look of the Meadows is obvious.

From Edinburgh's Green Heritage by Ian Nimmo

Reproduced Courtesy of The Recreation Department, City of Edinburgh

The archaeology of the Meadows landscape

The present layout of the Meadows is the result of several centuries of adaptation of the local environment. As is well known, the Meadows was a water-filled hollow which was only gradually drained and in filled.

Recent excavations on the north side of the Meadows revealed what appears from a distant inspection to be fine white riverine silt under a later deposit of heavier clayey soils. With such overlay of dumped material covering the original ground surface, there is little evidence of any earlier occupation or land use.

The draining of the Meadows began in the early eighteenth century and was soon followed by the creation of the primary element of what maybe termed its designed landscape: Middle Meadow Walk.

Created by Thomas Hope after 1722, this was essentially a raised causeway across the partially drained morass that was the remains of the former loch. This provided a path for the then fashionable exercise of strolling. This path was widened by the purchase of adjacent land from the George Heriot's Trust. In form it is outwardly a mere path, but it was conceived of as an improvement to the city, a route linking the urban centre with the countryside in a controlled civilized manner that would be appreciated by eighteenth century sensibility.

An undated letter of this period commented on how Mr. Hope had beautified the Meadows wonderfully and made it into another St. James Park (NAS GD189/2/164).

Avenues were an essential feature of the great gardens of this period, emulating the great gardens of Versailles. The walk was carefully laid out with the spire of St. Giles as a focal point at its northern end. Its southern end, at least in the early nineteenth century, terminated at the Cage, a sort of summerhouse that acted as a place of refreshment.

Middle Meadow Walk, therefore, was not just a path but was conceived of as a garden walk, a stretch of nature tamed and civilized. It is the tradition of great avenues with monumental foci, either existing or created for the purpose.

Scottish examples include the gardens of Kinross House, focused on Loch Leven Castle, and Newliston with avenues aligned on historic structures including Alloa Tower.

In the urban context Middle Meadow Walk may be compared with the great Parisian avenues that radiated out from the centre of the city, where walking was a fashionable activity. In London, The Mall, laid out in 1660, and St. James Park, once a water meadow like the Meadows, offered similar facilities. New Walk, York was laid out along the riverside in the 1730s for the fashionable recreation of the inhabitants.

Middle Meadow Walk was laid out by Thomas Hope as a thirty foot wide walkway, enclosed on each side by a hedge and lime trees. The walk also was to be bordered by a narrow canal, nine feet wide. Ornamental canals were a feature of the great European gardens of the period. The remains of a double bank can still be seen flanking Middle Meadow Walk in its central section, especially in low light; this is probably the remains of the canal, a feature that still fills with water after heavy rain.

The depth of the Meadows before infilling can be seen on the OS 1:1056 town plan of Edinburgh of 1849-53. This shows a water pipe, now underground and recently renewed, as passing over the Meadows raised on a covered conduit with a dry arch under its deepest park, in the centre of the Meadows.

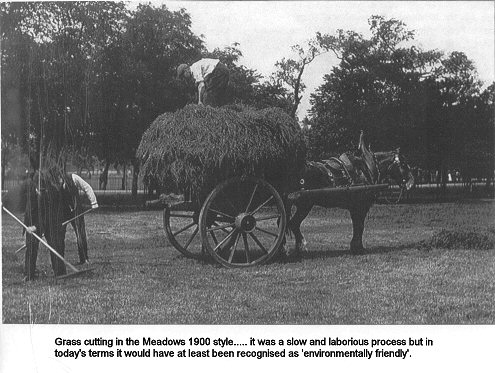

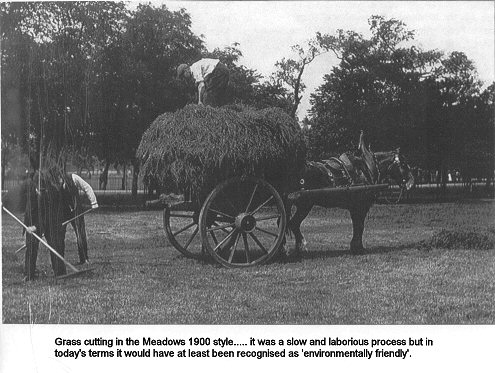

The 1849-53 plan also marks a 'sheep ree' on the west side of Middle Meadow Walk about where the information board has been erected. A 'ree' was an enclosure for animals; and the sheep may have served the role of environment-friendly lawn mowers. The eastern end of the Meadows is covered with a large area of posts, over 100 in eight rows. These may have acted as a huge drying green, although a more industrial use such as bleaching is a possibility.

Dennis Gallagher

Edinburgh International Exhibition

This link leads to our page about the Edinburgh International Exhibition, 1886.

Helen Acquroff Fountain

Click here to go to our page about the Helen Acquroff fountain.

The Nelson Pillars

Click here to go to our page about the Nelson Pillars.

At the junction of Middle Meadow Walk and North Meadow Walk is a five panel mural.

You can read about it here.

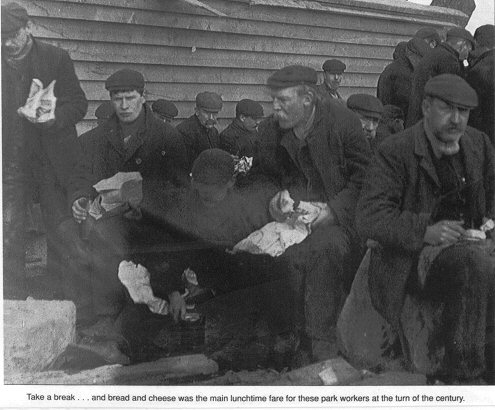

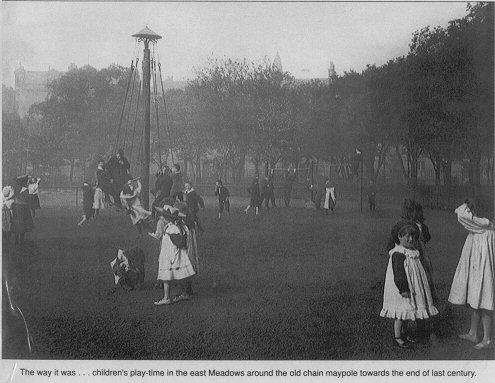

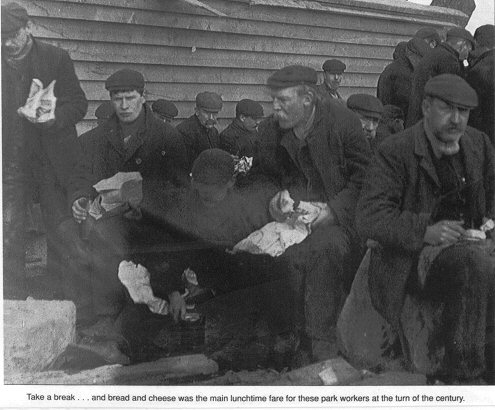

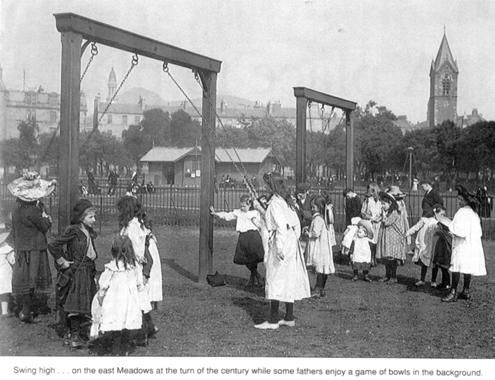

Here are some historical pictures of the area